Click the images in this post to see full-sized renderings.

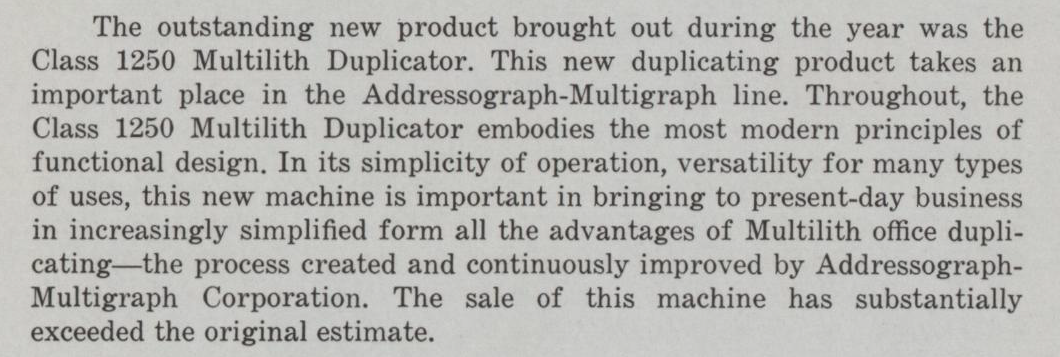

June 29 2020 marks the centennial of the birth of Ray Harryhausen (June 29 1920 – May 7 2013), iconic pioneer (though not inventor) of stop-motion animation. Most science fiction fans are familiar with his filmography, which spans four decades (1942 – 1981).

As with many of the genre writers, artists, editors and publishers who became prominent in the 1940s and 1950s, Harryhausen’s first involvement with science fiction was fostered by organized fandom in the 1930s. He connected with the active fan community in Los Angeles and became an early member of the local chapter of Hugo Gernsback’s Science Fiction League.

In Harryhausen’s own words, from a 1998 conversation with David A. Kyle, recorded and transcribed by John L. Coker III:

“When I was young my mother bought for me a series of books called Wonder Books. They had wonderful illustrations and photographs of strange things such as Egyptian temples, and charts on how long it would take to go to the Moon and to Mars and all the different planets. That started to stimulate my interest in science fiction.”

“Then, I saw Metropolis and Just Imagine and The Golem, all when I was very young. They had a real influence on me. We teethed on Frankenstein and Dracula.“

“I didn’t know much about stop motion at the time when I saw The Lost World. King Kong was the one that did it. It sent me spinning out of Grummen’s Chinese in a tailspin. I haven’t been the same since. This big gorilla was responsible for introducing me to Fay Wray, Willis O’Brien and Forrest Ackerman. I owe a big debt to this gorilla, who was fifty feet high, sometimes forty feet, sometimes thirty feet. He was a big inspiration to me.”

“I was more interested in the visuals than the science fiction literature, such as the covers of Imagination that Forry [Ackerman] used to publish. The magazine covers for Wonder [Stories] and the artwork of Frank R. Paul were a stimulus.”

“I became interested in Gustav Doré, and he was my mentor. He was a wonderful Victorian artist who was noted for his engravings, although he was a sculptor, an oil painter and many other things. I learned about Gustav Doré from Willis O’Brien.“

The Kraken debuts

More from Harryhausen’s conversation with David Kyle:

“In the mid-1930s when I was still in high school, Forry told me about the little brown room in Clifton’s Cafeteria where the Los Angeles chapter of the Science Fiction League would meet every Thursday. Members included Russ Hodgkins, Morojo, and T. Bruce Yerke. Robert Heinlein used to come around, and a guy named Bradbury. We were a group who liked the unusual. There was a fellow named Walt Daugherty, who was an anthropologist by trade, and a photographer. He would make presentations about Egyptology. Another young fellow named Ray Bradbury would arrive wearing roller skates. After selling newspapers on the street corner he would skate to meetings because he had no money. He used to go meet the stars at the Hollywood Theater where they did weekly radio broadcasts. Ray was writing for Forry’s magazine called Imagination. I did one of the covers for an issue, which was mimeographed.”

You may be thinking: The Kraken, you say? But, The Kraken didn’t appear until Harryhausen’s 1981 classic “Clash of the Titans.” We submit that the evolution of The Kraken occurred in clear steps beginning with Harryhausen’s 1938 cover for Imagination! For example, in October 1942, Harryhausen rendered this cover for the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society’s fanzine Voice of the Imagi-Nation.

Perhaps imprisoned by the creative gods, The Kraken railed at the bars of its watery cage for fifteen years. But in Harryhausen’s 1957 film 20 Million Miles to Earth, this charming Kraken progenitor (or spawn) emerged:

And again, in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad from 1958, another Kraken ancestor (or descendant):

The creature Harryhausen originally conjured from his imagination in 1938 evolved over the decades, until at the height of his powers in 1981, the ultimate Kraken was released.

How many times did Harryhausen see King Kong?

Fans had many opportunities to see the seminal 1933 icon of Willis O’Brien’s stop-motion animation, King Kong. After its original release, RKO distributed the film again in 1938, 1942, 1946, 1952 and 1956. Harryhausen was known to pursue these opportunities relentlessly.

In the Forward to Ray Harryhausen: An Illustrated Life (Ray Harryhausen and Tony Dalton, Aurum Press, 2003), Ray Bradbury wrote:

“My happiest memories are of Ray calling me during the years just out of high school and telling me that King Kong was playing somewhere, in some obscure theater in L.A., so we had to rush over and buy 15-cent seats to watch that glorious animal perform again…”

The count of Harryhausen’s viewings of King Kong became something of a legend within the Los Angeles fan community. Expanding reports appeared in fanzines of the period.

See below for the Popular Mechanics article.

Inspired by King Kong, Harryhausen began to experiment with animating his own models. Between 1938 and 1940, he filmed the ambitious short “Evolution,” featuring a dramatic Brontosaurus-versus-T-rex-versus-Triceratops battle. From his interview with David Kyle:

“I met [Willis O’Brien] when I was still in high school. He was my mentor. I noticed his name on King Kong, Son of Kong, and The Last Days of Pompeii. So, I called him up once at MGM when he was making War Eagles. He kindly invited me over to the studio.

“I brought over a suitcase full of my dinosaurs. I was particularly proud of a stegosaurus I had, for which I had won an award in an amateur contest at a local museum. I had made a diorama that I think won second prize. I was rather proud of it. He looked at it and said ‘Those legs look like sausages. You must learn to develop muscles. Every animal and every person has muscles to make the shape of the leg.’ I should have known this, but it was a shortcut. He said that I had to go to art school, so I went to high school during the day and went to art school three nights a week. USC started a course on film editing, photography and art direction and I signed up for it.”

Harryhausen as mask-maker

Harryhausen’s talent for model-making extended to masks. He contributed to the prankster culture in LA fandom by outfitting his fellow club members.

Ackerman later recounted the tale of his award-winning Harryhausen mask in Space Cadet n12:

“Ray Harryhausen chaneyed me into ‘The HunchbAckerman of Notre Dame’ in 1941 and his effective mask won me a prize at the 3rdWorld Science Fiction Convention that year in Denver. He started out to make me an ‘Odd John’ mask – albino hair, bulging frontal lobes, and all, as described by Olaf Stapledon in his superman novel of the same name – but the mask somehow came to grief (after quite a bit of grief of my own, lying on my back in his backyard, breathing through my mouth, my face baking in a plaster mold he was making of it, while his great dog Kong padded around occasionally sniffing me or licking my feet); the odd john mask was not completed to Ray’s satisfaction by the time of my departure for Denver and so a substitution was made of the Hunchback mask which he had previously created. I could only hope that my teenage years were going to turn out as cool as his. (They didn’t.)”

Harryhausen’s early art

Harryhausen’s occasional illustrations for fanzines reflected his passions for dinosaurs and macabre creatures.

Happy birthday, Ray!